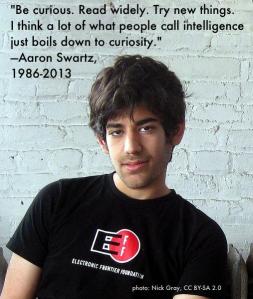

By Aaron Swartz. July 2008. Reposted to honor his goals, to remember him, and to motivate change in the justice system that failed him. His suicide is sad and deeply depressing – and it leaves no option for me but to kick and scream. This blog isn’t active anymore. but just before this tragedy hit I’d started a new project: hacktivity.ca. I’ll be channeling my thoughts there.

An inspirational thinker, and Open Access advocate. Thank you Aaron Swartz, may you rest in peace and may change come to the justice system that failed you.

Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations. Want to read the papers featuring the most famous results of the sciences? You’ll need to send enormous amounts to publishers like Reed Elsevier.

There are those struggling to change this. The Open Access Movement has fought valiantly to ensure that scientists do not sign their copyrights away but instead ensure their work is published on the Internet, under terms that allow anyone to access it. But even under the best scenarios, their work will only apply to things published in the future. Everything up until now will have been lost.

That is too high a price to pay. Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allowing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable.

“I agree,” many say, “but what can we do? The companies hold the copyrights, they make enormous amounts of money by charging for access, and it’s perfectly legal — there’s nothing we can do to stop them.” But there is something we can, something that’s already being done: we can fight back.

Those with access to these resources — students, librarians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out. But you need not — indeed, morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world. And you have: trading passwords with colleagues, filling download requests for friends.

Meanwhile, those who have been locked out are not standing idly by. You have been sneaking through holes and climbing over fences, liberating the information locked up by the publishers and sharing them with your friends.

But all of this action goes on in the dark, hidden underground. It’s called stealing or piracy, as if sharing a wealth of knowledge were the moral equivalent of plundering a ship and murdering its crew. But sharing isn’t immoral — it’s a moral imperative. Only those blinded by greed would refuse to let a friend make a copy.

Large corporations, of course, are blinded by greed. The laws under which they operate require it — their shareholders would revolt at anything less. And the politicians they have bought off back them, passing laws giving them the exclusive power to decide who can make copies.

There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture.

We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to take stuff that’s out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access.

With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us?

Aaron Swartz (1986 – 2013)

July 2008, Eremo, Italy

In memoriam

Recent Comments